To begin with, generations of whitewash and paint had to be scraped off the walls and antique wooden door and windows. These included the original staircases, banisters and carved wooden terrace railings. Termites had eroded the rafters, and the leaky roofs had to be restored. The main ceiling in the Durbar hall too, had been ravaged with time.

Renovations took longer than expected because the ceilings were high and required special scaffolding. Roofs in three rooms had to be completely re-laid. The lack of skilled workers meant that the artisans had to be brought in from the four corners of India: Rajasthan, Pondicherry, Orissa, Bihar and Delhi. They stayed on site for over a year, recreating the past glory of the rooms, bit by bit.

Another challenge was the relative unavailability of old finishes like Minton clay tiles, the six by six inch ceramic tiles and mouldings, and the mosaic chip flooring. Work slowed down, because these could not be easily procured or replicated.

In the end, the Minton clay tiles were matched to the same colour vitrified tiles, cut to size and installed. The mosaic flooring was re-created by an old craftsman, the last of the generation conversant with the art.

What stands out is the re-use of materials: Minton clay tiles in the verandah, Burma teak flooring in the main hall, mosaic chip floors and the thick wooden batons in the roofs. The Neemrana team has also restored the gilded and carved P.O.P. ceiling in the dining hall.

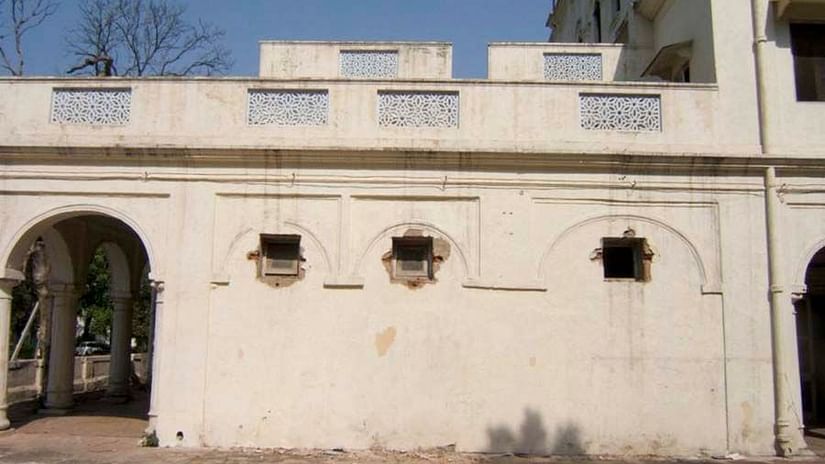

Today, a visit to the Baradari Palace transports guests to a bygone era. The Portico has cane chairs typical to old colonial bungalows. Period furniture and other vestiges of the royal past collected from everywhere, as well as a large collection of royal Punjab portraits make themselves felt throughout. The glass doors bear etchings of the Maharaja’s coat of arms. And at night the 12 cusped arches of the Baradari are illuminated, and a chandelier reflected in the mirror-topped tables casts its light on shadows of the past.